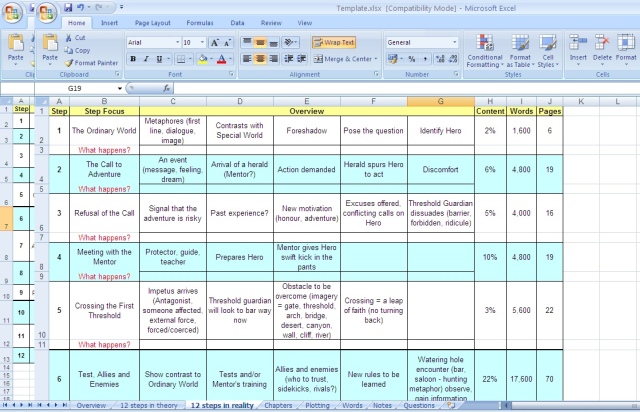

Before I move away from the Hollywood formula, there is another rule that is used for scripts that translates into a guide for novels (in my opinion). What is suggested in terms of content I agree with. The precise nature of when should be more fluid. It will make more sense once I get into it.

This aspect of the formula is a set of instructions that suggests specific moments when certain dramatic points show up in a story. It is recommended as a way to keep audiences (readers) engaged.

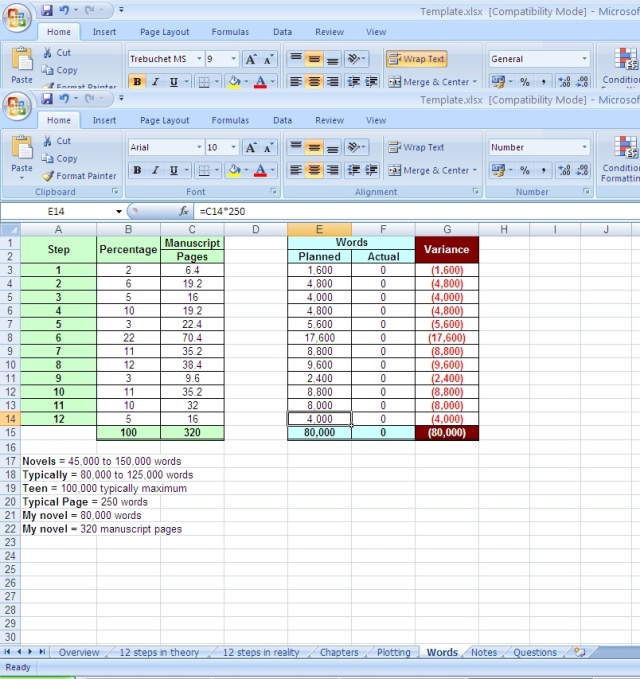

Suppose your book has 100,000 words (and each page has 250 words on a standard manuscript format). The Hollywood Formula suggests that on certain pages specific things need to be seen or be present. Use your calculator to change the page numbers depending on your planned book length.

They are:

Page 1: Geography (where the story takes place), tone and personality of story (mood.) And dramatic situation number one begins.

Page 10: The central question that will be explored is asked.

Page 33: Up to this page we need to know what the story is about, whose is the protagonist, who is the antagonist, what is it that each of these want and why can’t they do it at present. Dramatic situation number two begins.

Page 66: Dramatic situation number 3 begins (optional).

Page 100: The main character is challenged, he or she reacts and what is done can not be undone. Dramatic situation number 4 begins.

Page 150: Initial growth of main character. He or she matures in some way or form or learns something useful.

Page 200: Big trouble. The main character commits deeper to what he or she wants. The big trouble can also be a psychological conflict. Dramatic situation Number 5 begins.

Page 250: It looks like all is lost. The main character is just about to give up. Then, an event gives the possibility of solving the immediate conflict and accomplishing main goal. He or she reacts and what is done can not be undone.

Page 297: The main character grows again causing him or her to learn more about life.

Page 300: Great crisis. The main character leaves everything in pursuit of goal. He or she sees the main goal is achievable but there is a last obstacle. This event puts in jeopardy everything attained up to this point. Everything depends on this final moment, it’s all or nothing. Because of the action taken, the main character does or does not attain goal. Dramatic situation Number 6 begins.

Page 350: Introduction to the end. The main character grows again and because of this, learns something fundamental about life. At this point he or she may react again to some situation and what is done can not be undone. In many screen plays, this last dramatic turn is not needed and is optional. Dramatic situation Number 6 ends (optional).

Page 400: The end. By this point you have given the story introduced or promised by Page 33. The ending is closed so the reader is satisfied with the ending.

A closed ending means that whether it’s happy or not, we know what will happen after the book is finished. The closed ending can happen in any of the following levels:

– Story level: What happened before or what happens after the book

– Plot level: The immediate story, what the book was about

– Character level: What the character learned

– Ideology level: Codes of human conduct are questioned or reaffirmed